Kick drums are one of the loudest sounds in most electronic music (competing with the snare drum for that honour in some break-beat styles). A good kick drum can make the difference between a track that sounds just okay and one that provides hours of orgasmic listening pleasure. So I, and many other producers I know have spent hours trying to find just the right sound.

This document is optional reading: but it’ll help you make intelligent decisions and help you understand why some features are in the synth and why others have been omitted.

Inside an electronic kick drum

Most kick drum sounds can be decomposed into an attack portion, a kick body and sometimes some additional noise. Here are some views of a kick drum so you can see these parts separately.

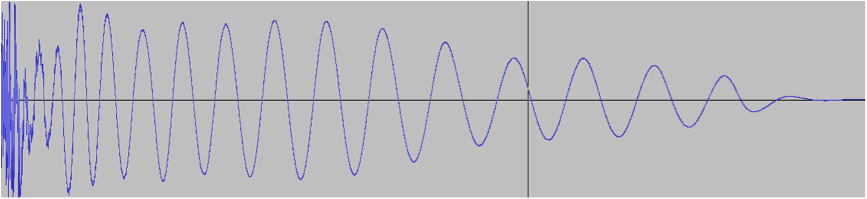

First, the usual waveform view of the a drum, the attack portion on the left, the body makes up most of the sound. The noise is pretty much invisible here.

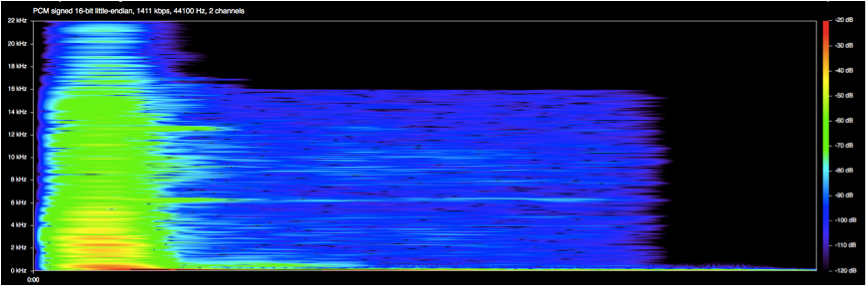

Now, a spectrogram. The spectrogram shows frequency on the vertical axis, and time along the horizontal. You can see the attack (big green bit on the left) with lots of energy all over the spectrum. Also, the noise (the extended blue area) which continues through the drum but is much quieter (hence blue not green) and finally the low frequency kick body (the thin green line right along the bottom).

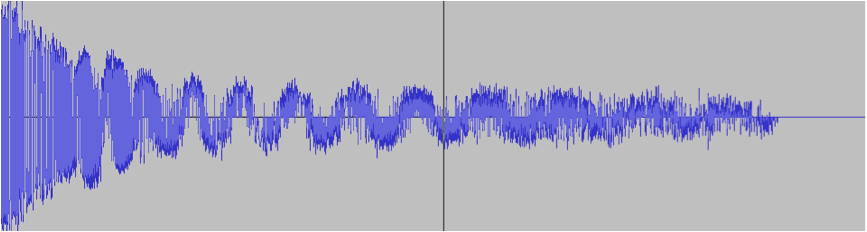

Finally, the same kick drum with a high pass filter applied. This removes most of the kick drums energy and lets you see the noise. The amplitude is shown on a log scale, which shows up the low volume detail more clearly. You can see that the filter I used wasn’t perfect. A little of the body is still getting through the filter (the low frequency wobble that’s still there!).

Understanding these three components helps us understand how best to construct new, great sounding, drums.

The Kick Body

In our deconstruction of the kick sound the body is the portion of the drum responsible for most of the acoustic energy: the bass heavy thuddy bit. It’s the part of the kick that needs to sit nicely with the bass, and whilst sonically it’s the least complicated it – it’s the most important.

The majority of electronic sounds, excluding some super-aggressive sounds, use a sine wave for the kick body.

The sine wave follows a sharply decaying pitch envelope. The pitch decreases rapidly until it settles on a low frequency (usually between 40 and 60Hz).

The speed and shape of this envelope and the starting pitch are critical for determining the character of the kick drum.

A tougher sounding drum may have a slightly less aggressive curve or perhaps a higher starting pitch. On the other hand a very tight electronic drum may have the high frequencies drop out very quickly and settle within a handful of milliseconds on the low pitch.

The settling of the pitch is either absolute – when it reaches the low frequency it just stops there. Or, like an 808 drum, continues to decrease albeit much more slowly.

If the pitch does settle on a frequency then it’s possible to tune the kick drum to a particular note – a technique that’s becoming more and more popular. Only some notes will have a pitch appropriate for a kick drum. The range of frequencies that sound kick-like is fairly narrow.

At the lower end it starts to loose depth, and there’s a lower limit on the frequencies that be usefully reproduced by sound systems. The (astonishing) Funktion One systems provide a subwoofer with a -3db point* of 25Hz, but more typically most good sound systems and large home speakers will roll off around 35Hz.

At the upper end, above about 65Hz, the drum stops sounding very much like a kick and loses the thud.

|

C1 |

32.7Hz |

|

Db1 |

34.7Hz |

|

D1 |

36.7Hz |

|

Eb1 |

38.9Hz |

|

E1 |

41.2Hz |

|

F1 |

43.7Hz |

|

Gb1 |

46.2Hz |

|

G1 |

49.0Hz |

|

Ab1 |

51.9Hz |

|

A1 |

55.0Hz |

|

Bb1 |

58.3Hz |

|

B1 |

61.7Hz |

* The point at which the energy has halved

The attack portion

On analogue electronic drum machines the attack portion is usually very simple. It’s often just a click supplemented by the start of the drum body. However since computers became the tool of choice the attack sounds have become significantly more complex.

The attack provides the click that cuts through the mix. For a harder sounding kick drum it might include a lot of low-mid energy (300Hz perhaps) and be slightly longer. For a softer but still tight kick it will probably be shorter or have less low frequency energy.

The attack portion can be almost anything, for example:

- A very short burst of white noise (a bit like the 909), or a single sample impulse (a bit like the 808), provides a suitable electronic fix.

- A compressed a distorted tom, or a snare drum.

- For a less aggressive sound, just a hi-hat works nicely.

The noise

Often some type of noise extends for the duration of the drum. This tends to be high frequency noise to avoid losing the tone of the kick body.

There are a couple of techniques I’ve used successfully:

- A touch of distortion on the kick body introducing some higher harmonics.

- Introducing some filtered noise over the top of the kick drum. White noise doesn’t make for a very interesting sound, but slowing down a sample until it becomes a low dirty tone, then applying some hi-pass filtering is a good starting point.

- Some time domain processing of the attack: Reverb, (short) delay or early reflections.

Again, all these techniques can be mixed, and there’s no single right way of doing it. It usually works best if the noise is very quiet.

Many kick drums are clearly layered with multiple attack sounds and noises.

Processing and editing

Once these basic components are in place, often further processing happens to the sound, primarily:

- Compression

- EQ

- Length adjustments

- Distortion

Most of us already have a favourite EQ. We haven’t tried to replace this with BigKick. If you do use EQ on the kick drum be careful adjusting the lower frequencies – EQ makes changes to the phase of the sound. Instead here are some suggested approaches:

Bass not right?

Adjust the volume of the kick, and then tweak the attack volume to get the balance right. If your kick has too much sub, or needs more weight change its length, or adjust the pitch controls.

Too much mid?

In the EDIT menu you will find three knobs: Width, Cut and Time. These allow you to reduce the volume for a portion of the kick drum. This provides a way of removing the mid from the kick drum without using EQ. It reduces the level at a position selected by the Time control.

Length adjustments

Longer kick drums sound heavier. But in some genres you want a particularly tight sound. Having two bass notes playing at once is often worth avoiding. It can sound muddy on a loud rig. Listen very carefully in a good pair of headphones – it may not be apparent on smaller monitors.

There are two main techniques: keep the notes short enough that they don’t overlap, or use a compressor triggered off the kick drum to turn down the volume of the bass when the kick drum is playing.

The compressor technique (ducking) is well documented on the Internet. Cutting the kick drum to length is made easier with BigKick. You can see the duration of the kick drum in 16ths in the display. Adjust the Hold and Decay knobs until it won’t overlap with your bass notes.

How does this work in Big Kick?

Big Kick uses a sample player for the attack and noise portions of the sound. There are too many variables and different characters to create a useful synthesis section. It has a high pass filter and decay envelope to enable to you to use almost any percussive sound you already have (including reusing other kick drums).

So … armed with all this knowledge what should you do? Well, you can:

- Load the kick drum presets and tweak them to taste.

- Select from the wide range of attacks we’ve already provided, and design the body of the kick drum to sit perfectly with your music.

- Create the perfect body in Big Kick and point the attack sample player at a folder full of kick drums you already have.

- Design your own attack sounds and use them to create a personal sound.